▲ This 1952 Vincent Series C Comet was sold by Bonhams (which supplied the image) in October 2012 for £19,550 including buyers premium. But standard it isn't. Rebuilt to what the seller called "Black Shadow specification", the engine capacity has been hiked to 572cc. Features include a 90mm JE piston, a Carillo con-rods, a Mark 2 camshaft, a Lucas SR1 magneto and a Dell'Orto carburettor. A Conway Motors Honda clutch conversion has also been fitted, and the front brakes have been converted to twin-leading-shoe operation with modified back-plates conversions.

Vincent Comet Series CVincent HRD and the Comet

High camshaft design

Series C Comets

Riding the Vincent Series C Comet

Vincent Comet maintenance Tuning for Speed by Phil Irving

▲ It's interesting that Vincent never affixed a cast alloy badge or similar to the petrol tanks of their bikes. Instead, they supplied ... a transfer. So was that a calculated weight saving consideration? Or just plain cheapskating? Or is a gaudy badge too downmarket for a motorcycle with such lofty ideals? Regardless, the Vincent name and reputation is much bigger than any badge, and we're all grateful for that.

Vincent Comet Series CSpecifications Type: Air-cooled OHV single Capacity: 499cc (500cc) Bore & Stroke: 84mm x 90mm BHP: 28 @ 5,800 rpm Compression ratio: 6.8:1 (optional 7.3:1) Transmission: Burman 4-speed, multi-plate dry clutch Brakes: Twin 7-inch sls drums front,

twin 7-inch sls drums rear Electrics: 6-volt, Lucas magneto, Miller dynamo Front suspension: Girdraulic Rear suspension: Pivoted action rear sprung, hydraulically damped Wheels/Tyres: 3.00 x 20-inch front, 3.50 x 19-inch rear Weight: 413lbs Maximum speed: 84-90mph

Vincent motorcycle contacts Bob Culver Telephone: 01462 673705 Vincent re-engineering specialist. Years of service and support. Friendly and approachable. Also does ally welding. Maughan Vincent Telephone: 01529 461717 Lincolnshire based Vincent engineers and parts manufacturers. Conway Motors

Telephone: 01732 842657

www.conway-motors.co.uk Vincent Owners Club

www.vincentspares.co.uk The Vincent Dot Com

www.thevincent.com Bonhams www.bonhams.com

▲ Like the Vincent Rapide, the Comet was supplied twin 7-inch diameter front brakes operated by rods, not cable. Hard riding will fade them, but for everyday touring purposes, you'll stop on demand pretty much wherever you need to.

▲ The original electrics were 6-volts and offered inadequate forward illumination for the twins, and slightly less so for the singles. Most Comets, Rapides and Shadows have been converted to 12-volts, and plenty of those with alternator conversions replacing the standard Miller dynamo.

▲ Tuning for Speed. Phil Irving's excellent guide on what makes a motorcycle engine walk and talk. Easy to understand information on both OHV motors and sidevalves. This is a masterclass read from a master engineer. Copies turn up every now and again. Buy one. Read it. Pass it on.

| The Vincent Series C Comet is the most numerous and most widely available of all single-cylinder Vincent motorcycles. The number built is generally quoted at 3,971. Introduced in 1948 and priced at £240, the Series C Comet was built upon an engine architecture that had been conceived 14 years earlier and which formed the basis of all subsequent motorcycles originating from the Stevenage, Hertfordshire based firm. Depending on whose version of history you accept, the Comet platform was either created jointly by company founder, Phil Vincent (1908-1979) and Chief Engineer, Phil Irving (1903 - 1992), or was designed solely by Phil Irving. Certainly much of the fundamental motive-power thinking was that of Irving's, a cool-headed and pragmatic Australian motorcycle engineer who had travelled to Great Britain in 1930 to develop and market his ideas. But Philip Conrad Vincent (PCV) was nevertheless a shrewd businessman and a forward-thinking motorcycle designer who knew what he wanted and had a plan to get there. And that plan had two central tenets: Build the best, and make the best better. It's inconceivable therefore that PCV had little or no input into the engine that was to underpin his company's fortunes. Or lack thereof.

▲1952 Vincent Comet Series C. We're so used to seeing Vincent twins and singles that we almost forget how ungainly and clunky-looking they actually are. Their riding characteristics are also a little ... different. In short, they're nothing if not an acquired taste, and one that most riders will never acquire.

The Comet platform was prompted by the general unreliability of 1930s motorcycle engine design when used in hard competition. In 1928, Phil Vincent had bought the name and rights to HRD, a motorcycle firm founded by popular racer Howard R Davies (HRD). Davies, however, had lost a lot of money on the failed venture, and PCV had arrived at the right moment with money in his pocket. HRD was an established brand, and Vincent wasn't. So the most expedient thing to do was attach the latter to the former until the Vincent name had sufficient marketing gravitas to fly alone.

▲ Vincent Comet Series C for 1952. The Comet was by now 4-years old, and it had failed to hit the sales numbers that Philip Conrad Vincent had anticipated. Two years later it was scrapped when the new Series D engines arrived, but only one Series D Comet was produced by Vincent at the Stevenage factory. However, after 1955 when the business folded, other Series D Comets were built from parts and they're still kicking around out there.

Both HRD and PCV had either witnessed, or had had first hand experience of motorcycle engine failures at the Isle of Man TT and elsewhere. The trading orthodoxy of the day was that to succeed in the showrooms, you had to succeed on the track. That meant that an engine rethink was needed if Vincent was to survive, let alone prosper. Phil Irving had joined the company in 1931 and began work on an entirely new power unit to fit within PCV's fairly radical cantilever front-and-rear-sprung rolling chassis ideas. Within three years, that engine was ready, and this new 499cc, single cylinder air-cooled unit became the Series A design. The engine featured, notably, a high camshaft arrangement with relatively short pushrods and twin valve guides for each valve. Between each pair of guides, a forked rocker arm operated each valve creating a robust, durable and reliable top end that obviated many, if not most, of the contemporary high performance failures (bent valves, high wear rate, over-oiling, oil loss etc). Phil Irving later further exploited this high camshaft principles during his time at Velocette. At the 1935 Isle of Man Senior TT, three such Series A HRD Vincents were entered, and although they didn't win, they all galloped home at, respectively, 7th, 9th and 12th place. And to merely finish a TT was a significant achievement in its own right. A short-lived Series B engine had been designed during the Second World War. But the next significant leap forward was post-hostilities when motorcycle production resumed in full at Stevenage. That was when, in 1948, two new bikes were launched: The Series B based Meteor and the Series C Comet. The Meteor was a touring roadster and was offered with a Brampton girder fork. The Comet was aimed at the sporting market and was offered with a Girdraulic fork. Both shared the "classic" Vincent spring frame. The new Vincents were displayed at the Olympia Show of that year.

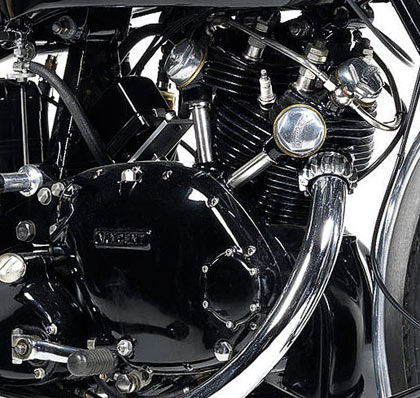

▲ The Vincent Comet engine cases were usually supplied in polished aluminium. The high camshaft design makes for shorter pushrods with less flex and less reciprocating mass. Designer (or co-designer: see text) Phil Irving practically wrote the book on motorcycle engine design and tuning. In fact, he did write a book: Tuning for Speed. Highly recommended.

The Series C machines carry the same bore and stroke of the Series A engines; 84mm x 90mm. This returns a capacity of 499cc and provides a respectable enough 28bhp at 5,800rpm. The cylinder head and barrel is cast from light aluminium RR53B alloy (the latter component featuring a cast-iron liner). The compression ratio is generally either 6.8:1 or 7.3:1 depending on original customer specification. But many bikes have since been owner-modified in line with available fuel changes and riding usage. The high camshaft (once referred to as "semi OHC") with two-guides-per-valve concept was retained. The carburettor is a single Amal 276. A Lucas KIF magneto supplies the sparks. A 50-watt Miller generator supplies the volts. This generator, note, is driven off the Comet's timing chest (unlike the dynamo on the twins which is spun by a sprocket driven by the triplex primary chain). Why the difference? Because the twin has an extra cylinder at the rear which requires a second camshaft, and that in turn requires a different dynamo drive. The Series C Comet clutch, interestingly, is not the servo-assisted design as fitted to the Rapides and Black Shadow twins, but is a more conventional multi-plate unit as found in the vast majority of British bikes of the era. A Burman 4-speed gearbox delivers the power to the rear wheel. A twin saddle by Feridax provides a convenient, if slightly lofty, perch for the rider. It pivots at the front immediately behind the fuel tank, and is supported on each side at the rear by a (adjustable) damped strut attached to the rear triangulated fork. It was definitely an unconventional arrangement, but it provided reasonable rider comfort when most British motorcycles offered sprung saddles and rigid or plunger frames. And today, it still provides reasonable rider comfort.

▲ The cantilever rear frame was a major selling point in its day. It makes for a slightly odd sensation at first, but after a few miles it's not really noticeable. Horse riders will settle in faster than most. Quickly detachable wheels are standard on Vincents.

▲ That large aluminium alloy cover at the front hides the 50-watt Miller dynamo. Footrests and pedals are adjustable. And a side stand is fitted on both sides. Vincent twins and singles are as much an academic exercise in engineering excellence as people carriers.

▲ That's a 150mph Black Shadow speedometer. A more realistic 90mph is what an average Comet rider will generally attain. But this bike has an upgraded engine, so it might well at least crack the "magic ton".

Classic bikers are frequently surprised at how crude the Comets can be on the move when compared to other British classic bikes of the same era. And not just the Comets. The big twins also display a certain unexpected ... quirkiness. Part of that is simply due to the Vincent myth which, like the Brough myth, has raised riding expectations to an unrealistic level. And part of it is simply that Vincents never come into their own until set-up exactly right and ridden with gusto, and many never are. Put another way, if you plod around town on either a Comet, a Rapide or a Black Shadow, you've got a carthorse between your legs, albeit a thoroughbred carthorse. But pay attention to the mechanical detail, crank one up, and you've got a racehorse, and then the unorthodox Vincent design makes a lot more sense.

▲ Ground clearance is generous 6-inches. Wheels are normally 3.00 x 20-inch at the front, and 3.50 x 19-inch at the rear. This example looks like its wearing heavier rubber at the back.

The Comet, however, offers a significantly rougher ride than the twins, which is perhaps no more than you'd expect for a torquey, 500cc single. However, they feel disproportionately rougher, largely because you need to make every power stroke count, and that makes them also proportionately noisier. Consequently, Comets deliver a slightly sharper exhaust bark, and with plenty of top-end clatter. The Girdraulic fork also earns its keep at higher speeds, and is less impressive at town velocities. Riders often talk about weave and wallow. But the Vincent fork is always more competent than the average Webb-type design, and better than the Brampton fork fitted to the 500cc Vincent Meteor. The Girdraulic damps better, is quieter and helps plant the bike more firmly on rough roads. But that fork doesn't excel until you're munching hard miles. And there's another factor to consider. Owners of Rapides and Shadows have in the past tended to put extra effort and cash into creating a precise riding set-up. That means having well maintained fork bushes, side thrust washers and front springs/dampers. It means keeping the pivots for the triangulated rear frame section (swinging arm) exactly within manufacturer specifications. It means selecting and maintaining the right rear springs and dampers; keeping that front seat pivot smooth and rattle free; and taking time to set up the (two) damped seat struts. Get one of these factors wrong, and you'll simply "know" it. Get it all wrong, and one way or the other you'll risk parting company with the bike. But until recently, many Vincent Comet owners were a lot more casual about such detail. The Comets, being that much cheaper, were commonly treated in much the same way that many riders treat Harley Sportsters. In other words, entry-level and not quite the real thing, and therefore unworthy of more serious detail work. However, as Comet prices have risen to more "realistic" levels, that attitude is changing, and it's far more usual to see Comets that are every bit as fussed over as the big twins, if not better.

▲ The Naugahide-covered Feridax Dualseat, note, is connected to the triangulated "swinging arm" by damped struts, and the centre of gravity is quite high. These factors help conspire to produce a novel riding experience until you adjust.

The controls are all fairly manly and spread your arms wider than normal across the classic flat Vincent handlebars The conventional multi-plate clutch can be a little grabby (possibly poor set-up once again). The gearbox is a typically competent 4-speed unit from Burman. The ratios on the Comet are about right for the street (we haven't ridden a Meteor), but overall, the transmission doesn't do much to add to the Vincent Comet cachet. It just works. The "Duo" brakes are good, but perhaps less than you might expect. Yes, in their day they were excellent. But times have changed. Traffic is heavier. The car in front stops faster than it ever could. And a hard series of hot, downhill bends will soon encourage you to back off a little and cool your wheels. That's why many Vincent owners opt for replacing the front back plates and fitting twin leading shoes, or (God forbid) even discs (which are probably overkill on most Comets anyway). But when set up right, you can throw a 500cc Comet around with confidence, and most riders will feel able to push them a lot harder than a twin and stay within their personal riding limits. Starting should be a first or second kick affair. The kickstart lever has a different swing to many other Brit bikes, note. It's shorter, and a little "jabbier". But it does what it's told to do, and if your ignition and carburation is in good order, and if your starting procedure is well rehearsed, you won't wear out your knees, or even boot soles in getting one warm. Beyond that, a sorted Comet should tick over evenly with instant throttle response. A sorted Comet should wake up properly at around 3,500 - 4,000rpm, and it should feel eager all the way to 90mph. The Miller dynamo is reasonably reliable. But regular touring riders will want a modern alternator upgrade. You'll never beg for a passenger. Like many of life's secret pleasures, it's often a ... ahem, solitary one. And if you ride two-up on a Comet, you're as good as hobbling yourself. Then again, on a Comet you could tour the world with a passenger and at least enjoy the satisfaction of travelling on quality hardware. Pretty much everything is adjustable, incidentally. Tommy bars are everywhere, and the adjusters click nicely into place. And much of the servicing/adjusting work can be done at the roadside without tools. But if you need a spanner or screwdriver or tyre inflator, check beneath the seat. Vincent thought of everything. Well, almost. Ultimately, it really all comes down to the looks and the badge on the tank. And if you do buy into the Comet experience, and if you buy at reasonable market prices (give or take a few thousand quid), you can't lose your money. Not so far, anyway.

▲ In April 2008, Bonhams sold this 1950 Series C Vincent Comet for £11,500 including buyers premium ...

▲ In April 2012, Bonhams sold this 1951 Series C Vincent Comet for £16,100, also including buyers premium. This example had only 7 miles on the clock since a thorough rebuild. Nevertheless, it highlights the fact that the Comet has been steadily rising in value.

Want more information? Okay, check out this link for the story of Rod Atkins and his high mileage Series C Comet. ▲ Top |